Plantationocene

In 2014, a discussion held by the interdisciplinary research group Aarhus University Research on the Anthropocene (AURA) generated the term “Plantationocene” as an additional critical counter-term to the controversial “Anthropocene.” As science studies scholar Donna Haraway relates, Plantationocene was meant to point to “the devastating transformation of diverse kinds of human-tended farms, pastures, and forests into extractive and enclosed plantations, relying on slave labor and other forms of exploited, alienated, and usually transported labor.” (Haraway 2016: 206) While early agriculture has long featured in scientific discussions about the putative start dates of the Anthropocene, the deep and accelerated planetary changes now unfolding are more often credited to the industrial agencies and processes of modernity. (Steffen, Grinevald, Crutzen & McNeill 2011: 847) The term Plantationocene reminds us that forms and practices of agriculture vary in their environmental impacts. The plantation system developed in colonial Brazil and spread across the greater Caribbean and North America is the early modern prototype for the highly industrialized, chemical- and petroleum-intensive, and bioengineered monoculture widely in operation today. As numerous TAAG interviews and glossary entries attest, there is wide interest among the gardeners and ethnobotanists of Geneva in the recovery and practice of local alternatives to industrial monoculture. Anthropologist Anna Tsing, also a participant in the AURA discussions, has emphasized the “scalability” of the plantation system as a key to understanding its profitability, its devastating human and ecological impacts, and its predominant grip on modernist corporate and governance cultures. Scalable operations can be expanded smoothly without changing their organization, and are thus well-aligned with the imperatives of capital accumulation. “In their sixteenth- and seventeenth-century sugarcane plantations in Brazil, … Portuguese planters stumbled on a formula for smooth expansion. They crafted self-contained, interchangeable project elements, as follows: exterminate local people and plants; prepare now-empty, unclaimed land; and bring in exotic and isolated labor and crops for production. This landscape model of scalability became an inspiration for later industrialization and modernization.” (Tsing 2015: 38-39) The plantation also points to the foundational violence of modernity, in the genocide of Indigenous peoples and the dispossession and enclosure of their common lands, and in the Atlantic slave trade and forced diaspora of Africans into “New World” plantations. The systems of racialized social control built on this violence have left persistent legacies of terror and trauma (Gilroy 1993), and processes of ecocide and cultural genocide initiated in the colonial and plantation periods arguably continue today in many places. (Ray 2016, 2017; Shiva 2012, 2015; Short 2016) While it had no formal colonies, Switzerland was not isolated from involvements in settler colonial projects. (Purchert & Fischer-Tiné 2015) One of the largest plantations east of the St. Johns River in Florida was named “New Switzerland Plantation.” The text of a historical marker there reads: « Francis Phillip Fatio, Sr., (1724-1811) a Swiss native, brought his family, slaves, and personal possessions here shortly after Spain ceded Florida to Great Britain in 1763. After obtaining a crown grant of 10,000 acres in this area, Fatio imported materials from England and built a country estate where he lived the life of a frontier baron.” (St. Johns County Historical Commission 1997) (GR)

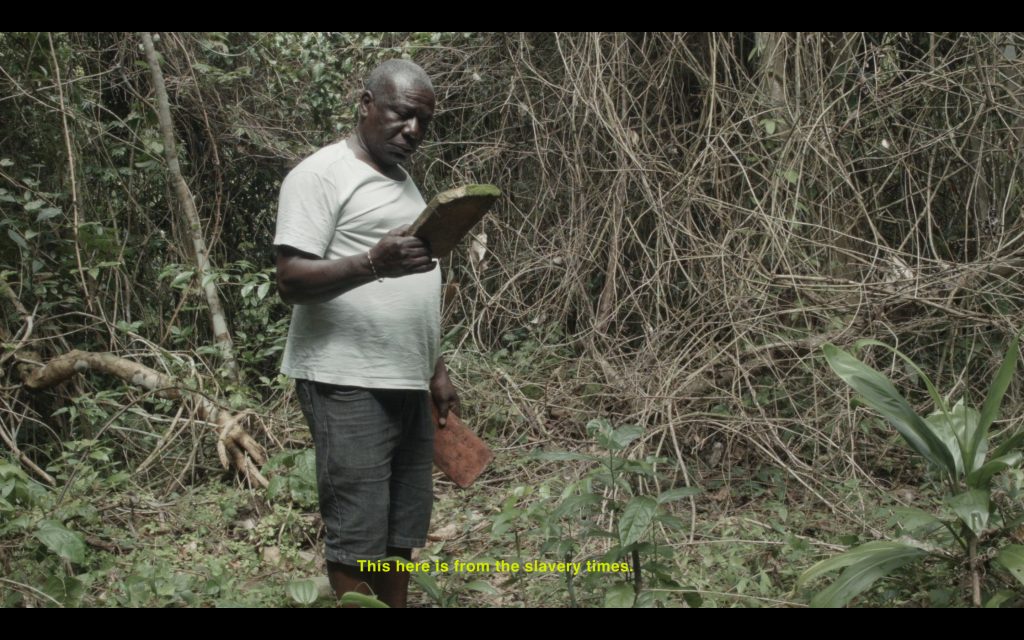

Images: Stills from Denise Bertschi, Helvécia, Brazil, 2017, three-channel video from the 2017 exhibition « Coffee from Helvécia » at the Johann Jacobs Museum, Zurich. Contemporary Helvécia, in southern Bahia, is a formally recognized quilombo, a community founded by former slaves. In the 19th century, Helvécia, part of the Swiss and German Leopoldina colony, was a large-scale coffee plantation. The Swiss-owned and -run plantation exploited the forced labor of approximately 2000 slaves. First coffee was exported from Helvécia to Europe, while later the machines for producing St. Gallen embroidered textiles were exported from Switzerland to Brazil. The wealth of the Jacobs family, which founded the Zurich museum, was accumulated through the commodity of coffee. Artist Denise Bertschi, a PhD student at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, researches Helvécia and the little-known history of Swiss participation in European colonialism. In addition to video work, she has made and exhibited embroidered white on white textiles based on archival stamps and documents linked to the Swiss Consulate in Bahia. The images below show details of her work, including the family names of Swiss colonial plantation owners. All images courtesy of the artist.

See also: Capitalocene, commodities trading, Necrocene

Related interviews: Victorine Castex, Denise Gautier, Denis Schneuwly, Arlene Shale